The Travis Pike's Tea Party

RIOT ON SUNSET STRIP, BLAST OFF GIRLS, and DISK-O-TEK HOLIDAY are all films from the mid '60s that are highly revered by collectors of

garage band music. While RIOT has yet to see an official video or DVD release, its reputation stems from the fact that it featured

appearances by three legendary bands: The Chocolate Watchband, the Standells, and the Enemys. BLAST OFF GIRLS and DISK-O-TEK HOLIDAY

garnered their cult following after being released to the home video market. Like RIOT, both films featured prime footage of authentic,

dye in the wool garage bands: Charlie and Faded Blue in BLAST OFF GIRLS, and the Vagrants and Rockin' Ramrods in DISK-O-TEK HOLIDAY.

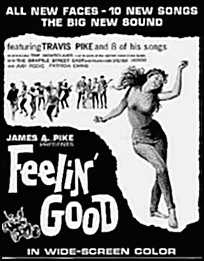

Another film that unfortunately has all been forgotten, but that also supported featured roles for '60s garage bands, was FEELIN' GOOD

(1966). Directed by James A. Pike, and starring his son, Travis Pike, the film featured the Montclairs, and Travis and the Brattle

Street East. Aside from starring in the film, the multi-talented Travis also wrote numerous original songs for the film, and later

went on to form Travis Pike's Tea Party, who cut one classic single, "If I Didn't Love You, Girl." Prior to starring in the film

and forming the Tea Party, Travis was a veteran of three earlier garage bands, and the author of over 200 original compositions.

Currently very active in the art of story telling and performing arts, Travis was gracious enough in providing The Lance Monthly

with a very detailed history of his stint in '60s bands, and in the film FEELIN' GOOD.

The Multi-Talented Travis Pike

One of Massachusetts's Standout, Music Contributors During the '60s

[Lance Monthly] Most of the people we interview for The Lance Monthly joined a band as a result of the rock and roll craze that started due to the Beatles' early success, yet you first joined a band in 1959. What were the circumstances leading to you becoming a member of the Jesters?

[Travis Pike] I was the quintessential alienated youth, a transplant from Roxbury to Newton Center, Massachusetts. For people not familiar with the Boston area, just imagine growing up in a condo in a deteriorating neighborhood and suddenly moving to a mansion in the most affluent area you know. I tried to make friends, but it seemed like every other day some new kid was being goaded into picking a fight with me. In retrospect, I suppose it was an attempt by the locals to deal with this scruffy interloper, to establish a new pecking order, but at the time, I thought it was the most cruel and stupid community in the world, a hell on earth to which I had been unjustly condemned.

I ended up spending a lot of time with my record collection. The very first record I ever bought was a 78 rpm by Somethin' Smith and the Redheads called "It's a Sin to Tell a Lie," but by the time I got to Newton, I was listening to Elvis, of course, and Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, the Coasters, the Everly Brothers, Little Richard, Clyde McPhatter (with and without the Drifters), Fats Domino, and The Platters. And while I was living in Newton I discovered The Kingston Trio live at the Hungry I, Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, the soundtrack albums from Ben Hur and Peter Gunn, Dave Brubeck's "Take Five," Dwayne Eddy and Marty Robbins' gunfighter ballads and trail songs.

Then, one day as I was walking home from school, a car with three kids in it pulled up beside me. I was instantly alert, ready for fight or flight, with flight seeming the best option. Two of these kids were BIG! And the biggest of them, Teddy Stanhope, asked me if I was Teddy Pike, the singer. Warily, I admitted to being Teddy Pike. Then the other big kid, Bobby Caron, said they had a band and they needed a singer and would I like to come to a rehearsal. Well, it was definitely better than getting jumped by three guys and beaten up. They were from Natick, two towns removed from Newton, and they really did have a band, a three piece combo, drums (Bobby Caron), electric guitar (Teddy Stanhope) and the third kid (whose name I forget) played saxophone. The microphone plugged into the old Fender amp was for me.

They played a few instrumentals, to warm up and convinced me they knew how, and they were good. I went from hoping I'd make it home alive to wanting to stay and show them what I could do. Teddy Stanhope had the Chuck Berry stuff down cold, so I started with Sweet Little Sixteen. When the song ended, we were all stunned, grinning stupidly at each other. They began asking me if I knew this song or that, and mostly, I did, and they played each one and I sang them all, right on the spot, while Bobby kept a list of each. By supper time, we had twenty or so songs down pat and a number of others we still had to rehearse. I went home, went through my record collection, made a list of the songs I'd like to sing and brought it to the next rehearsal.

Our first gig, a Saturday night sock hop in a Catholic church basement in Needham, was only two weeks after that first meeting. We arrived at the church and the priest in charge let us in, following us back and forth to the station wagon as we unloaded the drums and amplifiers and my precious microphone and microphone stand. He was laying down the law. There was no smoking allowed and no drinking. He would not tolerate any foul language. Once the kids paid to get in, they were not allowed to leave. If they did leave, they'd have to pay to get in, again. This was intended to discourage kids from hiding a bottle outside or sneaking out for a smoke. If he told us to stop playing, we were to stop immediately. And there was five bucks in it if we did a good job. Mind you, I was only fourteen years old, not exactly a career criminal, and terribly excited about singing my first gig, so although I heard it all, it didn't mean anything to me. I wasn't nervous. I knew the songs and we'd played every one on our list at least a few times. And I was "out of town," so nobody who knew me would be there. If it didn't work out, nobody would know.

Finally, it was time to start. The crowd grew quickly. A few danced, but more simply stood, wide-eyed, clapping along with the music. We came to our first break. I didn't know what broke. I thought we were doing well. The "break" meant we could help ourselves to free punch and go over our song list to make up the next set. It was also when the kids talked to us, asked us who we were, where we were from, [and] when we went back on, did we know this song or that and would we dedicate "I'm Just a Lonely Boy" to Joey. I couldn't help but notice when it was time to start again, the crowd had thinned out rather dramatically. But I sang "Lonely Boy" for Joey, or whomever, and the crowd began to swell, again, even bigger than before. By the end of the second set, quite a crowd had gathered, but I saw a bunch of kids rush out, as soon as we announced our break. Well, it was almost ten o'clock, so if I thought about it at all, I probably thought they just had to be home by ten. By the time we started our third set, we were playing request after request, some of them songs we'd already played, others, songs we had never even rehearsed! And the crowd grew and grew! Before we finished, the room was jammed and jumping, bright eyes gleaming everywhere and I was soaring through the songs, no longer merely mimicking the originals, but substituting lines and making up words on the fly for songs I didn't know except for the chorus

At eleven o'clock, it was over. Under the stern eye of the priest, the kids disappeared quickly. We packed up, generally pleased with ourselves, thinking it had gone pretty well. Then the priest told us that he'd never had such a crowd at any sock hop the church had sponsored. He said kids had left during the breaks to get their friends and paid to get back in. Some had left and returned twice! He only promised us five dollars for gas, but he gave us twenty and promised that he'd have us back again!

[Lance Monthly] The Jesters were together only briefly, and broke up when a member that used to drive the band to rehearsals and gigs found a girl friend. Were you extremely disappointed, or did you know you'd move on to other bands?

[Travis Pike] I was devastated. I had been given a chance to belong, an opportunity to shine, a situation in which I was not only tolerated, but admired. And I had been learning new songs, listening to records over and over, writing out the lyrics, practicing the words and melodies. I was ready to rock and roll and it was all gone in an instant. I didn't know any other musicians and I didn't play an instrument myself. And at fourteen, I had no transportation. I thought it was all over.

[Lance Monthly] After the end of the Jesters, you joined the Navy and, while stationed in Germany, wrote "Demo Derby," the theme song to a 28 minute feature that played across the nation in more than 6,000 theaters with A HARD DAY'S NIGHT. The song was performed by a band named the Rondels. What do you recall about them?

[Travis Pike] Well, before I joined the Navy, I had high school to finish, and I wrote "Demo Derby" before I went to Germany, but you're right about the rest. As for the Rondels, I really don't know anything about them, although I might have met all of some of them at one time or another. I was already in Germany when my father made DEMO DERBY, based on my song and a story idea we had discussed before I left. The song you hear in the movie was arranged and produced by Arthur Korb and he selected the band to record it.

[Lance Monthly] While in Germany, you became a member of the Five Beats. How did that band form, and why were you billed as "The Teddy?"

[Travis Pike] I arrived at my remote duty station in the North of Germany in October 1963, with a smattering of German I picked up in High School. In my off duty hours, I hung out in an ice cream parlor in the picturesque little city of Lutjenburg, Ost Holstein. The combination of my fractured German and the cleverness of the kids, all of whom studied English in school, allowed us to communicate pretty well, especially when I drew cartoons or we talked about American rock 'n' roll and hot rods! I helped them understand the lyrics to the songs that played on the jukebox and they corrected my German and taught me the words for the parts displayed in my hot rod magazines - which is how I met my good friend, Frank Dieter Andres, a journeyman auto mechanic with a fanatical interest in American rock 'n' roll. Of course, I had to tell him all about The Jesters.

In mid November, there was a Kinderfest, a children's day celebration in which the kids marched through the city and up to a German army camp where there was to be a big party in their honor. The kids I knew from the Eis Cafe implored me to come along as their guest, and when Frank said it was all right, especially since the whole town was going and there'd be nothing else to do, anyway, I went along. A trio of German soldiers (guitar, bass and drums) was playing music for the kids and before I realized what he was up to, Frank was introducing me as an American Rock 'n' Roll star! It was no use trying to back out. The grinning kids would not be denied! I sang "Heartbreak Hotel" and the kids and their parents both went nuts! I sang a few more songs and that's all there was to it.

A week later, the assassination of JFK drove it all from my memory. Nevertheless, by the following spring, I was being regularly invited to sing with bands in local clubs and dance halls and I later learned it was all as a result of my performance at the Kinderfest. Everyone from the local troops to the parents and grandparents of the young adults and children had heard me sing and obviously wanted more! I do not know if the tale I am about to tell came about because I misspoke myself, or someone just invented a gig for me, but that spring, on both Pfingstagen (Whitsun Saturday and Sunday), I was booked and publicized to appear with two different bands at two separate locations, several miles apart! A compromise was struck. Ernst-Gunther, son of the owner of Gasthaus Schroeder, Behrensdorf, would pick me up at the Koralle in Ploen after my first set with "The Nightstars," drive me to Behrensdorf where I would appear as the special guest of "The Vampiros," then return me to Ploen for a last set with "The Nightstars," wait for me and bring me back to Behrensdorf for a last set with "The Vampiros."

The attention was flattering, but the wild rides through the stormy night, slipping and sliding on high-crowned cobblestone roads between the two venues, were real white-knucklers, both for me and for the fellow who rode back and forth with Ernst-Gunther, rock promoter Werner Hingst. Werner was terrified and swore he'd never do it again and that became the basis of his proposition. I was a super talent, he said, but I needed management and he was just the man for the job. He would book me all over Germany, all over Europe! I'd be as big as Freddie (then the reigning German pop star). And I would never have to do this running-back-and- forth-between-bands business again. I would have my own band. He'd help me put it together.

Did I think any of the guys in either of the bands I was playing with that night were good enough? As sorry as I was to burst his bubble, I told him I was in the Navy, on active duty, and not available for such bookings, but Werner was an entrepreneur and would not be dissuaded. He'd put the band together and book them independently. They'd be available for my recording sessions, but I would have to agree to appear with them, as a special guest star from the USA, whenever I was available. It was heady stuff, especially that business about recording. I agreed to proceed, one step at a time. During the second night's performances, I was actually auditioning the two bands, although they were not told. When it was all over, I told Werner that German drummer Norbert Wechselbaum and Italian bass player and singer Enrico Lombardi, of "The Nightstars," were both outstanding. Lead guitarist and singer Wilfried Kuhn of the Vampiros (who went by the stage name of Eddy Christers, was talented, as was rhythm guitarist Norbert (who called himself Chorty West), and "Charly Ross," the saxophone player. If Werner could put them all together, we might have something.

I don't know what inducements Werner offered, but the young men I selected all showed up to rehearse with me in a big dance hall in a hotel in Preetz. They all knew what I could do, but they were ill at ease and distrustful of each other and Werner, until they started to play. By the end of the rehearsal, we knew we had something extraordinary. These guys really were the best of the bunch and they rocked! We couldn't wait to run through the numbers, creating a list, just like the Jesters had done four years earlier. Werner wanted me to take them beyond the music. He wanted a show band. Well, the guys were up for it, so I came up with ideas for skits, blackout numbers as they were called way back when. For the Jungle Show, they dressed in phony animal skins and for the Bedouin Show, they put on burnooses. I honestly can't remember what songs we played to go along with those costumes, but I think I probably sang Ray Stevens' "Ahab the Arab" for the Bedouin Show. The Vampiros had these bat winged capes they hung from their guitars. Rather than discard them, I came up with a Vampire Show. I needed something spooky to go with the look, so I taught them "Love Potion Number 9." I added a little maniacal laughter and it worked, especially for a crowd who didn't understand the lyrics. They would have to rehearse without me during the week, but we'd all get together on the following weekend for our first big gig, back at Gasthaus Schroeder, Behrensdorf.

As I left the hotel, there was a small crowd outside. To my astonishment, they booed me! The young man who had played double necked electric guitar and bass for the Vampiros, confronted me. How could I do this to him? Who was I to say who could be in the band and who couldn't? Dismayed by his pain, I offered that he should try to get together with the other guys from "The Nightstars," but he rejected the idea. He was one of the founders of The Vampiros and had poured his heart into the group. He'd be there at Gasthaus Schroeder to witness my downfall. The new band, who had just elected to call themselves "The Five Beats," would be decisively rejected by the loyal Vampiros fans. I hadn't given a thought to the pain it might cause the band members, especially the ones who didn't make the cut, nor had I given any thought to the fact that both bands were regionally well known and both had loyal fans. I was merely answering Werner's question. Shaken by the enormity of what had been done in my name, in my behalf and at my behest, I told the young man that I hoped he would come and hear the new group, as my personal guest. He spat on the ground, turned his back on me and walked away.

The following Saturday night, for the first time in my life, I experienced that "hole" in the pit of my stomach. I was not suffering from stage fright. I had complete confidence in The Five Beats, but I did feel guilty about what I'd done and that young man's wounded face was ever in my mind. When Werner introduced us, there were no wild cheers, just a murmur of anticipation and hostility like I had never experienced before until the band started to play. Eddy sang a song or two, then Enrico. They both did well, but the crowd withheld their approval. Werner said I better go on. I chose to open with Ray Charles' "What'd I Say" and had the band start without me. At the appropriate moment, I sprang onto the stage and went right into the song. I kept that song going for more than twenty-five minutes, all the while springing and dancing and playing with [the] audience, even finding the angry young man in the crowd and involving him directly in my performance, holding my microphone out to him to sing the responses--which he did--and when I finally finished, I brought the house down! That one song completed the set and when I got off stage, I thought my heart would burst right out of my chest.

It was several minutes before I was recovered enough to sit up. I left backstage to get a drink and there was the young man, grinning wryly, waiting for me to appear, offering me a glass of Sect (German Champagne). He embraced me and wished me the best of luck. He said he now understood why I had done what I had done. He was a trained musician, and although it made him sad to admit it, he recognized superior talent when he heard it. The Five Beats were superb and sure to go straight to the top. It was a gracious, sincere and most welcome gesture and from then on, The Five Beats and I only got better! As for being billed as "The Teddy," that really started because the Germans had trouble pronouncing Travis. In German, the "v" is pronounced like an "f" and because it is a foreign name, half the time they'd drop the final "s" and call me Traffy! Teddy was my nickname ever since I was little, probably derived from my middle name, Edward.

By happy coincidence, "Teddy Boys" were what the English called my generation of juvenile delinquents. Rock 'n' roll was equated with delinquency and danger by many adults, which is probably the single biggest reason, after the music, that adolescents are drawn to it. Under the circumstances, my childhood nickname signified youthful rebellion. I became "The Teddy," the epitome of the German "halbstarker," bearer of the forbidden fruit. For those who keep track of such things, the bifurcation between Mods and Rockers hadn't happened, yet, but I was firmly rooted in what was to become "The Rocker" camp.

[Lance Monthly] You were involved in a car crash in 1964 that spelled the end of your relationship with the Five Beats. At the time, I'm sure you were despondent, but do you ever look back at the time spent recovering as a blessing in disguise since it afforded you the time to compose many new songs? Or do you think the Five Beats could have gone on to many bigger and better things, especially since "Beatlemania" was just hitting?

[Travis Pike] Taking part two first, The Five Beats and I were ready to go mainstream on day one. In fact, I had secured the forms from the Navy to request permission to sign a recording contract. Scuttlebutt was that if I wasn't allowed to sign right away, the deal would wait for my discharge, when I could return to Germany as a civilian and pick up, full time, where I had left off. In fact, a few short months after I left Germany, The Five Beats did sign a recording contract with Phillips. As for being despondent, I was as crushed as my ankle. The deal had been for "The Teddy: die Twistsensation aus USA," a singing dancer with more moves than a long tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs.

I would never be billed as a "Twistsensation," again. I was in and out of the hospital for the next two years, suffering through a bone graft operation and more, but watching the bands come and go on Shindig and Hullabaloo was what used to bring me to the brink of tears. I think I did cry when I saw The Rolling Stones on Ed Sullivan. Of all the rising stars making it to the top while I rotted in recovery, Mick Jagger, although unique in so many ways, was also the heir apparent to my former stage persona. I won't go so far as to characterize my accident as a blessing in disguise, but the fact that I could not dance my way to success is what led me to learn to play the guitar. And performing for the wounded in Chelsea Naval Hospital is what got me writing songs and making up spoofs of pop tunes and that did lead to my coffee house career which, however convolutedly, eventually brought me back into rock 'n' roll, as a singer-songwriter. The truth is, there was more healing and restructuring going on at the time, than anyone, including me, ever realized.

[Lance Monthly] After returning from Germany, and while still recovering from the accident, you were asked to join the New Jesters for a high school talent show. Reportedly, the furor caused by your performance at the gig inspired your father to make the movie, FEELIN' GOOD. What was your father's movie experience prior to FEELIN' GOOD?

[Travis Pike] That's another entire book! In short, when he was fourteen, he began making silent movies, some of which were shown locally in the Boston area. While still a teen, he wrote, directed and performed in a Boston weekly radio broadcast. After WW II, he went to WNAC-TV, channel 7 in Boston, where he became director of programming. He was one of the people who brought movies to television and won awards for various TV specials he produced for the "Yankee Network." He was a vice president by the time he left WNAC to found Pike Productions, the company he still heads that provides theatrical policy trailers to theaters in the USA and several countries around the world. His first independent theatrical release after leaving WNAC was "Demo Derby," the black and white crash action featurette that opened with Robin and the Seven Hoods and then played around the country with the Beatles, "Hard Day's Night." "Hard Day's Night" was a black and white film that ran a little short by our theatrical standards and "Demo Derby" was the perfect compliment to it, extending the overall runtime of the show to two hours.

[Lance Monthly] You wrote eight songs for the film. Can you tell me a bit about them?

[Travis Pike] The title song, "FEELIN' GOOD," had a soulful, driving rhythm, so we asked the Montclairs to perform it, along with one of their standards, George and Ira Gerschwin's "Summertime." English folk singer, Brenda Nichols, performed "Ride the Rainbow," one of her original compositions, in a coffeehouse scene that I only just now realized strangely foreshadowed my own, real-life comeback. I sang seven of my original songs in the picture. "The Way That I Need You" and "Wicked Woman" would have been great Elvis songs and were deliberately derivative. They were meant almost as a salute to the King - and the Brattle Street East did a good job on both. My "Don't Hurt Me Again" could have been written for the Everly Brothers or Ricky Nelson and "Watch Out Woman" and "Ute, Ute" (in German), were songs I composed with the Five Beats in mind. "It Isn't Right" was an odd blend of rock 'n' roll and regionalism that worked well enough in the movie, but never quite worked for me, musically.

If a single song best characterizes "FEELIN' GOOD," it is "I Beg Your Pardon." (No, I'm not apologizing for the movie!) "I Beg Your Pardon" was a totally unique ballad, created especially for a romantic scene on the Swan Boats in Boston's beautiful Public Gardens. The arrangement is a bit strange, but it is a Boston fantasy and the Swan Boat sequence is a highlight of the film, generating many an audience sigh, especially among older viewers. Admittedly, I have to share credit with the Swan Boats, and Patricia Ewing, the lovely young lady who played my female lead, but "I Beg Your Pardon" was special. I almost forgot "Foolin' Around," another "light" rock tune. All the rock tunes I sang in "FEELIN' GOOD" are a little on the light side and I just remembered why. Musicians will cringe, but it's important to remember that "FEELIN' GOOD" was a movie, first and foremost, and the songs were performed to suit the film, not the other way around. Well, the drummer in the Brattle Street East fretted that if he played sitting down, no one would see him through the crowd, so my father, who directed the film, said he could play standing up and that's the way he played the songs in the recording studio, too, so the playback would match the visuals!

[Lance Monthly] What do you recall about the Montclairs? The Brattle Street East? You performed in the film backed by the Brattle Street East. Had you performed with the band either before or after FEELIN' GOOD?

[Travis Pike] I wish I had the movie on video so I could check the credits. I don't remember their names, but The Montclairs, were three velvet-voiced Black singers (two of whom looked like twins), backed by a White, jazz trio. When they won the 1965 JayCees Battle of the Bands, they also won cameo performances in "FEELIN' GOOD." The Brattle Street East were never serious musicians, but a group of students from Harvard University who played frat mixers to make money on the side. I don't remember their names or how they were cast for the film, but they were authentic amateurs. They played well and provided "Jordonaires" style backup vocals, which fit well with the movie, but we never performed together outside the film and I suspect they all went on to graduate and seek careers in other fields.

[Lance Monthly] Did FEELIN' GOOD receive a local/regional release only? Any interesting stories you can relate about the film? When was the last time you viewed it?

[Travis Pike] I haven't seen the movie in more than 30 years, although my father did screen it for my daughter some 25 years ago, when she went back East on summer vacation. It was regionally released across the nation, and it was even held over in Denver, but we all suspect that was due to a lack of product. After the tremendous success of DEMO DERBY, FEELIN' GOOD was a disappointment. Although he never said so, I think one reason my father made the film was to help in my rehabilitation. I had been transferred to the Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia and he flew me home on weekends to be in the picture. I could barely walk and it shows in some of the scenes. He also thought "FEELIN' GOOD," an East Coast City movie could compete well with the then popular West Coast Beach movies. I had some suggestions, of course, but he was sold on the local writer who thought my "continental notions" were too sophisticated for mainstream American audiences. In fact, the kids were way more sophisticated than the adults believed. Nevertheless, some parts of the show were clever and funny, especially the documentary style bits about Boston, but the saccharine boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy wins girl back story line was uninspired. In all fairness to my dad, there wasn't much plot to the Beach movies, either, but what he and the writer both failed to realize was that by 1966, the Beach movies' day in the sun was over, too.

[Lance Monthly] After FEELIN' GOOD, you started performing at coffee houses such as King Arthur's, and the Sword In The Stone. How did this come about? Did you continuously write new songs during this period?

[Travis Pike] When I returned to Newton after being discharged from the Navy, I was again a "Stranger in a Strange Land." The country was suffering through the pain of the Vietnam War, but I was personally appalled by the way returning servicemen, who had served their country with honor and courage, were being vilified by their former school chums. I suppose I became reclusive, just me and my guitar, composing songs about lost loves, missed opportunities and times that never were.

A friend from high school dropped by and I played him a few songs. He must have thought they were good, because he invited me to come with him to a hootenanny at "The Loft," a popular Charles Street coffeehouse in downtown Boston. Anyone who signed up could play and there was a cash prize for the best of the night. I had a pretty low opinion of protesting folk singers who had never stood a watch, but I could always leave, if I wanted. There were a few good pickers and a few good singers, but by the time I went on, I was ready to start a fund to get Michael an outboard engine for his boat, for fear he'd never make it to shore! I did an off-color parody of "Puff, the Magic Dragon" with which I had entertained wounded G.I.'s at the naval hospitals, then played two songs of my own. I not only won the $15.00 grand prize, but I was offered a day job at a recording studio and a gig at King Arthur's, a downtown combat zone bar that billed itself as a coffeehouse with a liquor license!

I accepted both offers. King Arthur's became my "home room," a place where I could play as often as I wanted, as long as I agreed to MC their hootenanny and fill in the gaps if there was a low turnout. When King Arthur's lost its liquor license, Mark, the owner, bought the old Turk's Head on Charles Street, reopened it as "The Sword in the Stone," and it became my new home room. The beauty of having a home room was that you could still play at all the other coffeehouses on your off nights, but you hired on as a headliner or guest performer and were paid! I also took the day job as manager at Lightfoot Recording Studios, where I was paid to answer the phone and book recording time during the day. It was a perfect situation for me. Neither job paid much, but in addition to meeting and sitting in with dozens of promising musicians, I had all day to write and record my own songs, free! And it gave me a base of operations and rehearsal space when I finally did get around to starting a new rock group of my own.

[Lance Monthly] In 1967, you formed Travis Pike's Tea Party. Please list the members of the band, and the instruments they played.

[Travis Pike] Karl Garrett, an excellent classical guitarist and trained arranger studying at the Berklee School of Music in Boston, had been invited to study with Andre Segovia in Spain, but when he heard the demos of the original songs I recorded at Lightfoot, he "signed on" with me instead, as a backup singer and lead guitarist. Next on board was Mikey Joe Valente, bass player from the New Jesters, who had played with me on that magical night at Natick High School. When he heard I was putting together a band, he showed up, bass and amp in hand, ready to rock. Karl auditioned him and said that he was fundamentally sound and with some technique, which Karl could teach him, he was a possibility. Not content with that, Mikey Joe cemented his place in the band by finding the rest of the group for me. Phil Vitali, the drummer, was ex-Navy Band and his beat was as solid as a rock. He and George Brox, another singer and a rhythm guitar player, were in another band when Mikey Joe brought Karl and me to hear them. They were impressed by my demos and the fact that I could offer a recording studio for a rehearsal hall, but I think they were most impressed by Karl's playing and the fact that he was in the group and would be doing the arranging for us.

[Lance Monthly] The group is best remembered today as a psychedelic band due to its appearance on some '60's compilations. However, reviews of the time wrote that "Travis Pike's Tea Party performed in about every conceivable pop style from straight rock to psychedelic to folk to rinky-dinky ragtime." How would you best describe the band's sound?

[Travis Pike] Original. We played all original songs, almost all of which were my own compositions. Otherwise, the reviewer had it exactly right. Our repertoire was eclectic. Our ballads left people in tears, our novelty songs left them rolling in the aisles and when we rocked, we rocked the house down. Our vocal harmonies ran the gamut from rockabilly to rhythm and blues. Some songs were throbbing walls of sound, others were light and airy and still others were instrumentally humorous. My compositions were program music in which the lyric, melody and rhythm sprang fully developed from the same source and Karl's arrangements realized the potential in each composition. We were a concert group, not a nightclub act or dance band.

On any given night, we were apt to spontaneously transform into any number of surprising configurations, depending on the song, the venue and the audience. Phil was our drummer, and he would sometimes perform extended drum solos that culminated in incredible double bass drum rolls he played with his feet that left audiences thunder-struck, but when a song called for it, he'd come out from behind his drum set to play vibes and George would put down his guitar and sit in on drums. I picked and strummed 12 string and six string guitars for some songs, but just as frequently I played cow bell or tambourine or some other off-the-wall instrument or device best suited for the particular piece. And sometimes, especially when a string or drumhead broke or we were having some other kind of technical difficulties, the music would stop altogether and I would just tell stories.

If there was a gap in our concert bookings, Karl, Mikey Joe and Phil sometimes performed separately as a jazz trio and George and I both occasionally performed solo in local coffeehouses. George sang and played popular folk songs and I performed my original ballads or revisited my pop parodies. Karl sometimes played breathtaking solo performances of classical guitar and lute pieces. With so much versatility, both individually and as a group, we were tough to pigeonhole. Our fans loved us just the way we were, but our eclectic repertoire frightened off most record labels. We defied classification. We didn't fit into any niche they knew, so they didn't know how to sell us. We were a concert oriented rock group, ear candy, music for your mind as well as your feet. Always original, always fresh, always exciting, we were Travis Pike's Tea Party.

[Lance Monthly] During your time with the Tea Party, you had over 200 original compositions under your belt. What do you attribute your prolific writing to? Where did you draw inspiration for your songs?

[Travis Pike] Lyrics and melodies come easily to me, and composing new material for Travis Pike's Tea Party was my passion. As band leader, lead singer and songwriter, I was free to compose anything that moved me and the band could and did sing and play anything I could invent. Songs that other bands would never dare attempt were simply challenges to my lads. There were struggles, to be sure, and never enough money, but we were all doing what we wanted to do, and there was always that jackpot at the end of the rainbow.

[Lance Monthly] The Tea Party went on a promotional cruise with the Rockin' Ramrods in order to promote a local radio station (WRKO). What do you remember about the cruise? About the Ramrods?

[Travis Pike] The truth is, we went on the cruise to promote Travis Pike's Tea Party. We had originally called ourselves The Boston Massacre, but the Cheetah, in New York City, said they would never book a band with that name for fear of a riot, so after some deliberation, we settled on Travis Pike's Tea Party. The WRKO promo served to reintroduce us to our fans under our new name. In fact, there were two boats and the Rockin' Ramrods were on the other boat. I never met them and never heard them play. I thought they were an instrumental group, but I've been told that they sang and played all the hits of the day, which would have been a lovely compliment to us if we had all been on the same boat. We did a show like that at M.I.T., with Horne's Forest, a pop band playing top forty tunes, and the crowd loved it. When Horne's Forest was on, they could relax and dance to familiar hits, and when they were ready to listen to "something completely different," we were there to tickle their minds.

[Lance Monthly] Where was the band's only single ("If I Didn't Love You Girl" b/w "The Likes Of You") recorded? Do you recall the circumstances that led to the single being recorded for the Alma label?

[Travis Pike] We recorded both tunes at Joe Sayer's AAA Recording Studios in Boston, where we'd been recording all the music for the WBZ TV Series, "HERE AND NOW." In fact, that's how the record contract came to pass. Joe had heard of us, of course, and when we showed up at his studio, he was immediately impressed with our musicianship, especially Karl's arrangement of "Love is Blue." I told Joe that he had a unique opportunity, right in front of him. Here we were, with a TV show and no records to promote. If he wanted to record and release our songs on his label, we certainly had a showcase! He agreed to back a single and together we chose "The Likes of You and "If I Didn't Love You, Girl." for our first release on Joe's Alma Records label.

Incidentally, "If I Didn't Love You, Girl" is an excellent example of what I meant about us playing anything and everything I could

invent. In "If I Didn't Love You, Girl" I was exploring the defensive schizophrenia inherent in a teenage love affair. Really! And

the way I did it was to have the chorus, sung by Karl Garrett and George Brox, sing lyrical counterpoint to the principal lyric line,

thus, the chorus sings "I - - - didn't love you, girl" while I sing "I wouldn't cry all night, if I didn't love you, girl." In the

second verse, the same phenomenon is revealed when the chorus sings "You - - - really loved me, girl," while I sing "You would be

true through and through, if you really loved me, girl." The idea is that the wounded youth "subject" of the song must maintain

this dual psychology, so that if the girl ultimately rejects him, he can claim he was never serious about her, all the while he

is hoping desperately to keep her affection. You could dance to it and never give it another thought, or you could listen to it

and just enjoy the sound, or you could really listen to it and hear what I was saying. If you made it all the way to level three,

you were a Travis Pike's Tea Party fan. If anyone wants to hear it, an MP3 file of the original Alma recording is posted at

www.long-grin.com/~travpike/Tea-4.html

[Lance Monthly] Travis Pike's Tea Party performed music for the local TV show HERE AND NOW. Did the band appear at all on the show, or simply provide the music?

[Travis Pike] We appeared, performing, in all three shows, although only two shows ever aired. In addition to an instrumental cover of whatever topped the pop chart that week, I know we played "If I Didn't Love You, Girl" on one of the shows and may have played "The Likes Of You," too.

[Lance Monthly] Why did the Tea Party head to California? Was this 1968? How long did it stay?

[Travis Pike] When the 1968 TV show "HERE AND NOW" proved too controversial for "there and then," it was canceled. Karl and I had signed on as the music directors and the band was committed for the run of the show. It was canceled at the beginning of the summer, and all the summer gigs were already booked when we found ourselves out on the street. We'd be all right, if we made it to the fall when the college crowd came back to town, but we had to find a way to make it through the long, hot summer. I was hoping the record could keep us busy with promotional appearances, but then two things happened that forced me to take drastic action. WBZ Radio, until then one of the most powerful rock 'n' roll stations in New England, and part of Group W, who might be expected to throw us their support, bowed to the sudden strong competition from WRKO and switched to "Easy Listening!" And Harvey Mednick, the program director of WRKO, now the single most powerful voice of Rock 'n' Roll in the New England area, refused to play our record, no matter how many phone in requests he got. He considered us traitors. We'd gone over to the enemy (WBZ-TV) and he was determined that we'd never be heard on WRKO! It was a triple disaster from which there was no feasible recovery.

Roger LaChance, a friend and fan who had moved to the West Coast, dropped in to see me and to pick up a copy of our record. I told him what had happened and he said if I could be ready in three days, he'd bring the whole band back to California with him! He was sure we'd blow them away in L.A. In fact, I couldn't get everybody together in three days. George Brox had gone to the Cape and was nowhere to be found. Karl Garrett had students and a classical concert coming up, and couldn't get free for at least two weeks. Phil Vitali was married and had to see to packing up his whole household, which he couldn't do unless he was sure there was work waiting for him in L.A. So, Mikey Joe and I packed up and made the trip west, to reconnoiter and line up some gigs. Armed with our many demo recordings, it wasn't hard at all. The Youngbloods had either canceled or been canceled and there was an opening in a few weeks at the Whiskey A Go-Go. I arranged for Karl to fly out and I used the second half of his round trip ticket to fly back to find George and help pack up Phil. I couldn't find George, so I called Karl and asked him to find and start rehearsing a singing, rhythm guitar player to take George's place. By the time I drove back to California, Mikey Joe and Karl had found a replacement for George. Lonnie Hillard looked good and sang well, but was a slow learner. It was clear we would not be ready on time, so I had to cancel the gig at the Whiskey. Cash was running short. The pressure to get to work right away was enormous. The quickest and simplest thing to do was to get a gig playing top forty tunes that Lonnie already knew. Then, once everybody was working again, he could learn my original songs. The Posh, a big dance club in Pomona, California, was the first to sign us on as a house band, but we had to agree to play top forty tunes for the first twenty minutes of each set, before I could come on and we'd get to play our original songs. That was no problem. Lonnie knew and could sing all the current hits. The problem was that the band ended up spending all its time rehearsing top forty tunes and Lonnie made little progress with our original material. I stopped writing new songs for the band. There was no point. We had no time to practice the old ones. Oddly enough, the most requested songs we played, even in the clubs, were our own, but financial necessity was slowly transforming Travis Pike's Tea Party from an all original concert band into a top forty club band. We fell to bickering. Plots and counterplots emerged. That same financial necessity kept us together a while longer, but we'd come to the beginning of the end.

[Lance Monthly] Did you join any bands after the Tea Party disbanded?

[Travis Pike] No. I tried a few times to start new bands, but couldn't ever find the right combination of musicians. I suppose my heart just wasn't in it. As much as I missed Travis Pike's Tea Party, its demise did prove to be a blessing in disguise. I learned notation, which set me free from the tyranny of having to maintain and depend on a band. It also freed me to hire the best musicians, as needed, and record or sell my songs whenever, wherever and to whomever I pleased. I got over my disappointment and moved on with my song writing, poetry and prose.

This seems like an appropriate place to bring our fans, old and new up to date. I hear from Mikey Joe from time to time. He quit music after the band dissolved and went into business. It was Mikey Joe who told me George Brox died, some years ago, of cancer. No one knows what happened to Lonnie, but Phil rejoined the Navy. He retired a few years back, settled in Cape Cod and is now playing drums in the Rick Britto Jazz Quartet.

I found Karl at www.phillyguitar.org He still teaches classical guitar and is president of the Philadelphia Classical Guitar Society. As for me, I'm all over the Web, mostly under my full name, Travis Edward Pike. MP3 files of some of my post Travis Pike's Tea Party tunes may be found at www.morningstone.com If after reading this lengthy interview, anybody still wants to know more about me or my recent history, they should be sure to check out my 1997 "happening" at www.grumpuss.com.

"Copyrighted and originally printed on

The Lance Monthly by Mike Dugo".

"Listen live, online to their music at

Beyond The Beat Generation, 60's garage and psychedelia".